Culture and preferences towards collaborative learning methods

by Jagat Kunwar, Senior Lecturer, Xamk, Business & Culture

Introduction

Increasing internationalisation of higher education and cross migration of international students has facilitated intercultural contacts among students and the possibilities to implement peer group methods in education. There are several advantages and disadvantages of peer-group learning methods where the members belong to different cultures. For example, collaborating in a multicultural peer groups can help to generate diverse perspectives but there are also possibilities of negative learning outcomes due to cross-cultural conflicts. It is therefore vital to understand whether students from different cultures exhibit varying degree of preferences and experiences regarding collaborative learning methods with their peers.

The study

Recently I conducted a study to understand how cultural background of students can shape their experiences and preferences regarding collaborative peer learning methods. I surveyed randomly selected 147 international students studying at different Finnish UASs in total.

I used Geert Hofstede’s six dimensions of culture to understand the cultural differences among students. According to Hofstede, cultures can be differentiated in terms of several dimensions, such as:

- whether they favour individual achievements (individualist) over collective goals (collectivist)

- whether the society has differential power relations (hierarchical) or is mostly equal (egalitarian)

- whether the society espouse masculine values (favouring efficiency) or feminine values (favouring overall well-being)

- whether the society tolerate risks (low uncertainty avoidance) or favour high degree of certainty ensured through mutual rules (high uncertainty avoidance)

- whether the society is conservative (looking backwards) or progressive (looking forward) depending upon their time-orientation and finally,

- whether the society value short-term needs satisfaction (needs indulgent) over saving for the future (restraint).

The national culture of Finland, for example, according to Hofstede is inclined towards individualism, egalitarianism, focus on well-being, favouring certainty, progressive and favouring short-term needs satisfaction. The national cultures of several south Asian countries–e.g. Nepal, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh–are diametrically opposite to that of Finland on all of these dimensions. Cultural orientation of all individuals belonging to different nationalities can be categorized in a similar way based on measures of Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, which are available at Hofstede insights.

To understand the students’ experience and preference of collaborative learning methods, I implemented a survey containing various Likert scaled statements related to various processes in peer learning groups. The processes considered included communication, decision-making, leadership, evaluation, trust, disagreement, scheduling and persuasion in a peer group.

Surveyed students

In my sample, there were altogether 147 (N=147) respondents from different countries. The top nationalities of students were Finland, Russia, China, Nepal and India. The number of respondents were equally distributed in terms of gender (49,7% male and 50,3% female). Majority of the respondents (57,1%) were between 21-25 years of age. 42,9% of the respondents were in their second year of studies, 30,6% in their first year and the rest of in their third year of studies or more.

41,89% of the students were categorized as egalitarian, the rest (58,11%) as hierarchical based on their nationalities. 56,76% of the respondents were collectivist, and the rest (43,24%) were more individualistic. Majority of the respondents (78,38%) belonged to feminine cultures and the rest (21,62%) to more masculine cultures. 58,10% of the respondents were from conservative and the rest 41,90% from short-term oriented cultures. Finally, 62,20% of the respondents were from cultures espousing instant gratification cultures whereas the rest 37,80% of the respondents belonged to more ‘restraint’ and saving cultures.

Significant results

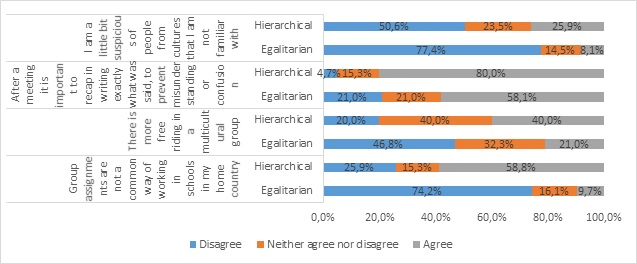

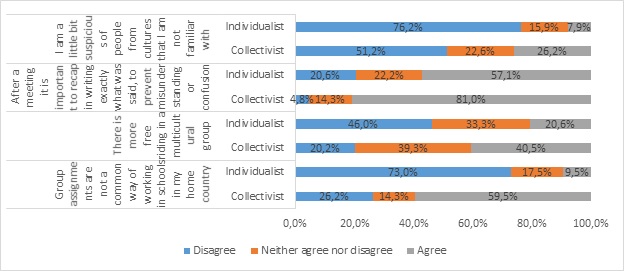

Cross comparing the students’ scores on their cultural dimensions and their preferences regarding collaborative learning methods involving students from other cultures, several key results were obtained. The results showed that the most significant factors, which affects students’ preferences and experiences regarding collaborative learning, are the egalitarian/hierarchical dimension and individualism/collectivism dimensions of culture. Both of these dimensions affect similar group processes (see figure 1 and 2).

A student belonging to a hierarchical (see figure 1) and collectivist culture (see figure 2)–such as India and China–had less previous experience with collaborative learning methods before coming to Finland. They also tend to suspect that people free ride in multicultural peer groups. Students from hierarchical and collectivist cultures also overwhelmingly prefer more structured and explicit forms of communication such as preparing a minute after group meetings to recap the main decisions made. The students from more egalitarian and individualistic countries– such as Finland–are more trusting towards peers from different cultures than their own, in comparison to students from collectivist and hierarchical cultures.

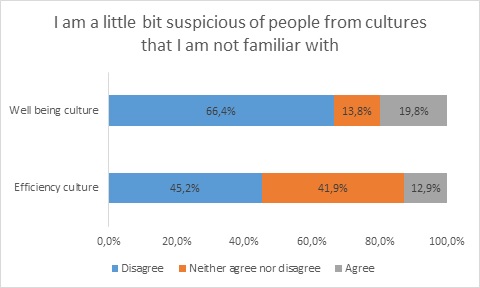

The lower degree of trust towards peers from other cultures than their own is also associated with whether a person belonged to a masculine culture–preferring efficiency or feminine culture–preferring overall well-being in the society (see figure 3). The results show that students from countries like Finland and other Nordic countries, which score high on feminine values also generally tend to disagree more (66,4% vs. 45,2%) to the statement that they are suspicious of people from unfamiliar cultures.

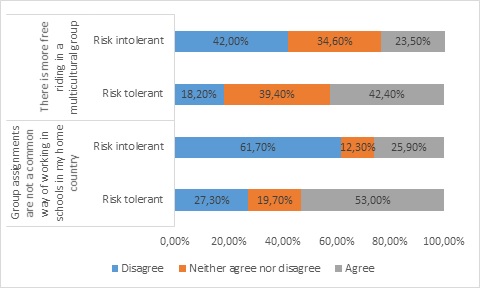

Whether the student were previously familiar with collaborative peer learning methods is also associated with whether their cultures score high on the uncertainty avoidance index–and hence, are risk intolerant or score low on the uncertainty avoidance index–and hence, tolerate ambiguities (see figure 4). Those students, who are from cultures that are more risk tolerant, seem to be unfamiliar with collaborative learning methods before coming to Finland. Students from more risk tolerant countries prefer to work alone, as they suspect that other peer group members will free ride on their efforts.

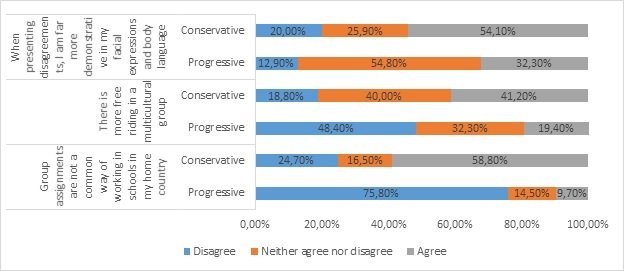

Lastly, the orientation towards time each cultures have also affected the way they dealt in collaborative learning groups. Students coming from cultures which value the past–and hence, conservative countries– showed slightly different orientations to peer learning methods in comparison to students who come from cultures who look towards the future–and hence, are from progressive countries. Iran is an example of a conservative country whereas Finland is an example of a progressive country. Students from conservative cultures have less experience working in a peer-learning group before coming to Finland and generally tend to avoid working in a group because they suspect that their peers will free ride on their efforts. Students from conservative countries also tend to be emotionally expressive of disagreements in comparison to their counterparts from more progressive countries (see Figure 5).

Some implications and conclusions

What does this all mean? The findings suggests that the students’ national culture is associated with previous experiences and future preferences regarding collaboration with their student peers. Students from hierarchical, collectivist, risk tolerant and conservative countries are less familiar with collaborative learning methods because they are not exposed to these methods in their own countries. Several middle-eastern countries and south-Asian countries are examples of cultures displaying such characteristics. Similar cultural clusters are also apprehensive of social loafing and free riding when they have to collaborate in a multicultural group.

Egalitarian, individualist and well-being cultures are more trusting towards peers from cultures other than their own in comparison to their opposite counterparts. Hierarchical and collectivist cultures also prefer more structured communications and decisions regarding group works. Students from progressive countries–such as Finland–should also be prepared that students from more conservative countries–such as south east Asia and the middle east–are more demonstrative of their disagreements through facial and bodily gestures.

These findings were based on the study of 147 random students currently studying at various Finnish UASs and hence, may have limited generalizability in other contexts. However, it clearly suggests that when we implement peer-learning groups–either as a pedagogical tool or at work–cultural experiences, preferences and expectations should be taken into consideration for more effective collaborative outcomes.

- Learning and Growth Mindset - 13th September 2024

- Another successful meeting – IBSEN meets XAMK in Kouvola, May 2024 - 16th May 2024

- Blending and joining the Finnish work life - 8th December 2023